A brief history of Ukraine

Trying to consolidate 1,200 years of history into a few minutes’ read inevitably simplifies a lot of very complex, interdependent events and leads a lot of stuff out. But I think this is a fairly objective primer.

In the 7th-9th centuries AD, the Vikings explored extensively along the rivers of what are now Russia and Ukraine, seeking trade routes from Scandinavia to Constantinople. Around 900 AD the Varangians (a Viking tribe) took control of Kyiv and made it the capital of “Rus”, their already-massive kingdom extending from Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. How a handful of Vikings so quickly gained and then sustained ownership of such a vast Slavic territory is a matter of dispute, but it almost certainly involved more trade and strategic marriages than straightforward conquest.

In 988 AD, Rus’ Prince Volodymyr adopted Christianity, with the seat of Rus’ new Orthodox Church in Kyiv. The kingdom reached the peak of its power under Yaroslav the Wise in the mid-11th century, as shown in Map #1. It stretched from the Black Sea in the south to the Arctic in the north.. Rus was the “root” kingdom and nationality of what are now three distinct ethnicities: Russian, Belarussian, and Ukrainian. This is the core of the Russian argument that Ukraine is not a nation, and they have “always” been together. In fact, part or all of Ukraine has been entirely outside of Russian control for 733 of the last 785 years, and the modern Ukrainian language is much closer to Polish than it is to Russian. If Ukraine “belongs” with anyone (which it doesn’t), then it belongs with Poland, not Russia.

Map #1 above: Kyivan Rus at its height in the 11th Century AD, Kyiv near the southern border. (Source: World History Encyclopedia)

In 1169, Kyiv was sacked by rival princes from Suzdal, Vladimir and a new village called Moscow up in the kingdom’s northeast. They moved the capital up to their area. Civil strife continued until the Mongols showed up in 1240 and laid waste to everything — not just Kyiv and other cities, but the institutions that held such a vast empire together. it split into small principalities, each paying tribute to the Mongol Horde and focussed on their own local survival. Around 1300, the northern princes (then under Mongol domination) moved the seat of Rus’ Orthodox Church from Kyiv up to the northeast, where it remains today.

This is when Russia and Ukraine fundamentally diverged. In 1362, the Lithuanians defeated the Mongols in battle and took the Principality of Kyiv, then still on its knees with Kyiv in ruins. Poland and Lithuania united shortly thereafter through royal marriage, later formalized in the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (see map #2 below) which became one of the most powerful countries in Europe. It included most of modern-day Ukraine and Belarus but almost none of modern-day Russia. The Polish Commonwealth was remarkably enlightened, with an elected monarchy governing on the model of the ancient Roman Republic, and regions retaining substantial autonomy. The Poles actively encouraged restoration of Kyiv’s cathedrals, monasteries and other cultural monuments, which restored Kyiv as a cultural mecca and place of pilimgrage, if not (yet) an economic or political hub. This period significantly influenced the linguistic and cultural development of both Ukraine and Belarus — the nobles spoke the empire’s official languages of Polish and Latin, but amongst the masses, vernacular Ukrainian and Belarussian languages took shape that are in between Russian and Polish (Belarussian is closer to Russian, Ukrainian is closer to Polish). If you believe that 50 million Ukrainians have no right to self determination and they need to be someone’s colony (which I do NOT believe, but indulge me for a moment), then by any ethnographic / cultural / linguistic measure, Ukraine belongs with Poland, not Russia.

In Russia, meanwhile, the princes of Moscow were preoccupied winning independence from the Mongols (Ivan the Terrible finally accomplsihed that in 1486), and then subjugating Novgorod and other rival Russian principalities under despotic Muscovite rule. During the 1300s-1500s, Russia and Ukraine were completely separate and focussed in opposite directions. But in 1613 Russia emerged from a national trauma called the Time of Troubles, with a new Tsarist dynasty called the Romanovs, eager to conquer in every direction including Poland.

Map #2 above: The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its height, including the Ukrainian heartland

“Ukraina” means “Borderland”. 400 years ago it referred to a lightly populated area between the Russian, Polish and Ottoman empires which is now the modern Ukrainian heartland. It was inhabited by the Cossacks, bands of fiercely independent semi-nomadic horsemen. They had privileges in the Polish Commonwealth in exchange for military service. But in 1648 the Cossacks started a war for total independence, and in 1654 they sought Russian protection. This started a 13-year war between Russia and Poland which ended in stalemate.

In 1667 Poland and Russia agreed to carve up Cossack Ukraine between them (see map 3). Russia got Kyiv plus everything east of it (the "left bank” of the Dnipro River), while everything west of that (the “right bank”) returned to Poland.

Map#3 above: Cossack Ukraine divided between Russia and Poland

In the map below of eastern Europe in 1700 (Map #4), you can see that Kyiv and everything to the east of it was ruled by Russia at that time, but Lviv (then known by its Polish name Lwow) and the rest of western Ukraine were still part of Poland. Most of what is now southern Ukraine including Crimea were under the Ottoman Empire. Throughout the 1700s, Russia got stronger while Poland got weaker.

Map #4 above: Central-Eastern Europe in 1700 (Odesa didn’t exist until 1794, but it is included here for comparison / continuity purposes vis-a-vis the other maps)

In 1783 under Catherine the Great, Russia achieved a major milestone in their eternal quest for warm-water ports, when they captured Crimea and most of the north cost of the Black Sea from the Ottoman Empire. The Russians called this beautiful and fertile region Novorossiya (“New Russia”); a large part of it is now southern Ukraine. Previously it had been lightly populated because of constant conflict, but now millions of Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Greeks, Romanians, and many others flooded in, founding the port of Odesa in 1794 which became one of the world’s great “melting-pot” cities.

Meanwhile as Poland got ever weaker, its neighbours started carving “chunks” out of it. Poland got wiped off the map entirely in the Third Partition of 1795. Much of modern-day Ukraine went to Russia, but pivotally, Lviv and the surrounding areas of western Ukraine went into the Austrian Empire (shown in Map #3 as the Habsburg Monarchy). In Russia, Ukrainians were told they are “Little Russians” living in “Malorossiya” (“Little Russia”), and their language and culture were suppressed. Throughout the 1800s, as the Ukrainian national identidy became steadily stronger and more defined, Tsarist restrictions on writing, publishing or teaching in Ukrainian (or even calling this area “Ukraine”) got steadily stronger and the penalties for disobedience got stricter. But off to the West, the Austrians allowed all their numerous nationalities to speak, write and publish as they wished, so long as they remained politically loyal. This was to prove critical to the development of the Ukrainian nation.

The period from around 1820 to 1920 in Europe is often referred to as the Era of National Awakening, when millions across the continent were starting to define themselves by their language and nationhood rather than just their village and religion. Lviv and the rest of Austrian-ruled southwest Ukraine was a “safe haven” where Ukrainians could do that. Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko (who spent his life in the Russian Empire) was exiled to a penal colony in Siberia for writing pro-Ukrainian, anti-Tsarist poems in colloquial Ukrainian. But in Austrian-ruled southwestern Ukraine, his works and those of his peers could be published and taught freely, and easily smuggled over the border to Kyiv and beyond. In the East of Ukraine (ruled by Russia with a large ethnically Russian population), the colloquial Ukrainian language was heavily suppressed, with many people adopting Russian as a first language. Kyiv became bi-lingual.

Map #5 above: The three empires of Central-Eastern Europe from 1795-1914, with modern national borders superimposed in the solid black outlines

For comparison, look at neighbouring Belarus in Map #5. Belarussian is the third “root” nationalities from Rus, along with Russian and Ukrainian. Like Ukrainian, the Belarussian language sits in between Russian and Polish. Like Ukraine, Belarus was part of the Polish empire for centuries until Poland was carved out of existence in 1795. In 1795, all of Belarus was put into the Russian Empire as shown in map #4 above, and subjected to intense Russification and subjugation of its indigenous culture. Belarus had no equivalent of Lviv, no enclave in the Austrian Empire where its culture could be nurtured to thrive another day. And as a result, Belarussian culture was much more successfully supressed. In both 1918-19 and 1991-94, Belarussian nationalists sought to re-establish their culture, but it proved too big a mountain to climb. From 1992-95, 40-50% of Belarussian schoolchildren were taught in Belarussian. Now the figure is below 10%.

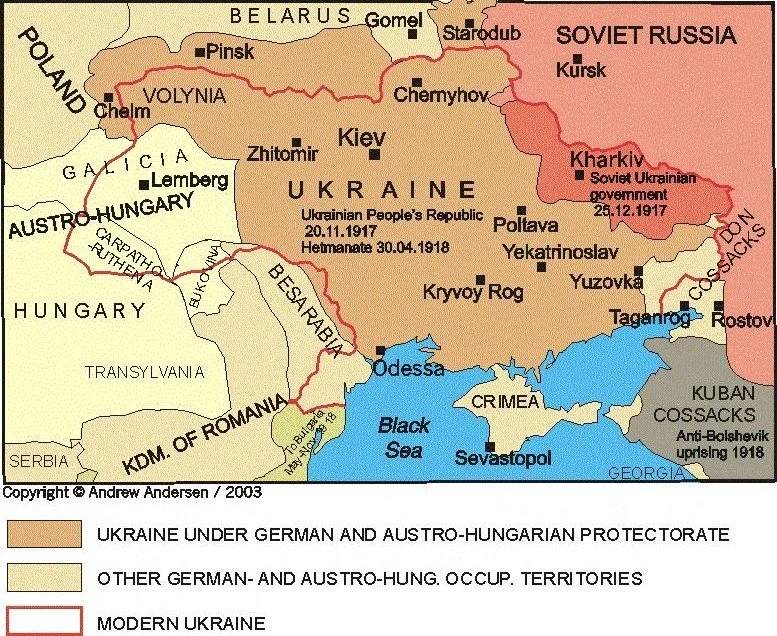

In 1917 Lenin took power and withdrew from World War I, accepting huge territorial losses. Germany and Austria occupied Ukraine and made it a “protectorate”. Ukraine then declared independence in 1918. Lenin created a small rival Ukrainian Soviet republic with its capital in Kharkiv, from ethnically mixed Russian-Ukrainian territory in the east (see map #6 below). In 1919 Poland was re-created as an independent country under the Treaty of Versailles. Independent Ukraine, the USSR (including Soviet Ukraine), and Poland all fought each other. Poland successfully reclaimed Lviv (Lemberg) and surrounding areas. In 1922 the independent Ukrainian state was forced to surrender to the Bolsheviks. Lenin merged the two “Ukraines”. Russification of Ukrainian lands continued, especialy so in the east.

Map #6 above: Ukraine from 1917-1922

The Holodomor (the “Great Hunger”) — Stalin’s mass murder of the Ukrainian peasantry

Marx had said that Communism was only for advanced, urbanised, industrialised societies. But the countries that adopted Communism (Russia, China, etc) had all missed the First Industrial Revolution, and adopted Communism hoping it would enable them to leapfrog into modernity. So Lenin changed Marx’s teachings substantially. Instead of the state withering away as Marx predicted, the state would be an all-powerful totalitarian entity dragging the rural peasants kicking, screaming (and often dying) into the industrial age. After taking power, Lenin enacted War Communism under which the peasantry were deliberately worked to death. Farmers were given impossible targets, and when the targets weren’t met the government took their land, livestock and seed corn. While the countryside starved, the Soviets exported massive quantities of grain for hard currency to buy weapons and machinery. Just like Mao, Pol Pot and so many other communists, Lenin and Trotsky were ashamed of their country’s peasant majority, who were clearly not the industrial proletariat that Marx had declared necessary for Communism. They saw this mass murder as toughening up inferior beings – the few peasants that survived would be fit for Communism, the rest deserved to die. (This became a role model that Mao, Pol Pot and many other Communists would follow in the future.) The idea of collectivising agriculture was not Marxist – Marx didn’t really care about agriculture. Collectivisation had been the norm in far northern Russia for centuries, because the climate was so hostile and crop failures so frequent that pooling resources was essential for survival. Lenin and Trotsky took this locally-managed, kibbutz-style model, ruthlessly centralised it, and imposed it on more fertile, southerly regions that had no use for it. The famine went on until the global price for wheat collapsed and Russia could no longer earn hard currency this way. Lenin then enacted market reforms under the New Economic Policy (NEP), a significant Gorbachev-style reform for which Lenin got a completely undeserved reputation as a moderate. He only enacted this reform because he had no choice.

Most of Ukraine had avoided the War Communism famine from 1918-22 because it was an independent country. And by the time the Soviets conquered Ukraine in 1922, the NEP reforms were already gearing up. But Ukraine’s turn was to come. In 1930, Stalin (now supreme dictator) decided another round of famine was needed, particularly targeting the Kulaks (relatively well-off, industrious private farmers who had done well under the NEP). Many of them lived in the fertile Black Earth region of Ukraine and southern Russia. Again, farmers were given unachievable targets. When they didn’t deliver, their land, livestock and seed corn were taken. To survive, they sold family heirlooms. The Communists set up trading shops called “Torgsin” where Ukrainians could barter their family treasures for whatever scraps of bread the State chose to offer them. These heirlooms were then sold abroad for hard currency. 3-10 million people died.

Picture of starving Ukrainians queueing to exchange heirlooms for bread at a Torgsin in Kharkiv. From the Holodomor Museum in Kyiv

Russians and Ukrainians argue vigorously over whether the Holodomor was a genocide. Ukrainians point to the staggering death toll, the deliberate mass murder, by any standard a holocaust. Russians say “yeah, but Russians were starving, too – it’s not like farmers with Russian IDs were exempt.” The Russians have a point that “genocide” denotes a race war, while Stalin’s target was an economic class – wealthy peasants of any ethnicity. The reason it disproportionately exterminated Ukrainians was that (1) millions of Russian peasants had been slaughtered already by Lenin and Trotsky during the first famine in 1918-22, so they didn’t need to be slaughtered again and (2) the lands where farmers most resisted collectivisation were the richest and most fertile lands, which are also the most southern lands. That includes only a portion of Russia but nearly all of Ukraine. You be the judge of whether this was a genocide. Without question, it rivalled the Nazi Holocaust in scale and sheer sadism.

Starvation victims lying in the streets of Kharkiv during the Holodomor. Exhibit from the Holodomor Museum in Kyiv.

My question to the Russians is “OK, if I accept your argument that it wasn’t a genocide and that you were slaughtered, too, then explain to me why you increasingly worship Stalin. What is it with Russians, that you worship people who slaughter you? Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Lenin, Stalin…. anyone who treats you like meat, you love them. Anyone who actually tries to improve your life, you hold them in contempt. If you admit it was a mass murder (which you do), why do you worship the man who perpetrated it?” The usual responses I get are “oh that wasn’t Stalin, it was the bad men under him” (Russians have an eternal need to believe in the “good czar”) or “oh, you foreigners just don’t understand”.

But I digress.

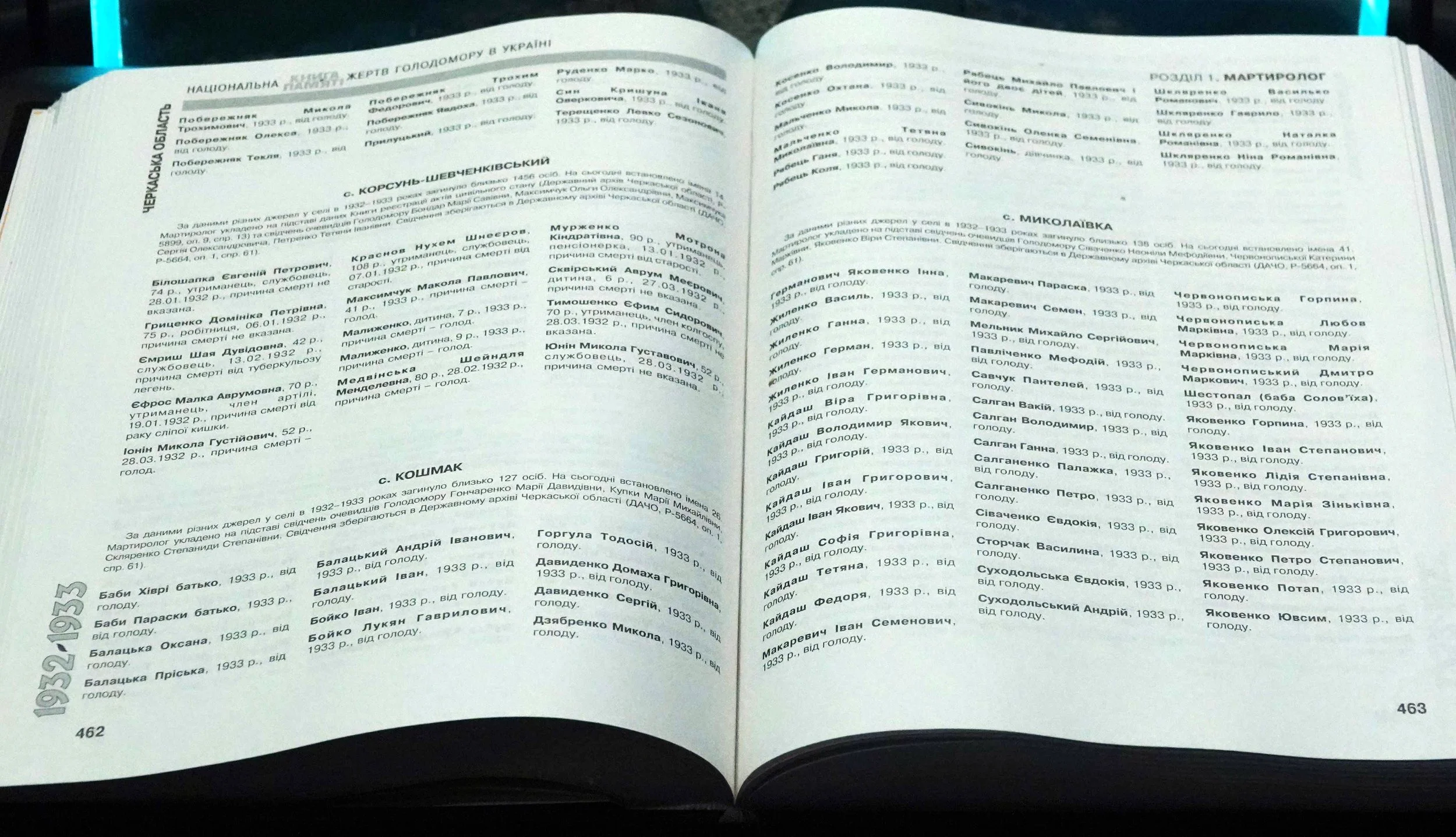

This 1,000+ page register lists the starvation victims in just ONE of Ukraine’s 24 provinces. At the Holodomor Museum in Kyiv

Just 6 years after the Holodomor ended, Hitler and Stalin made the Nazi-Soviet pact and carved up Poland between them. Under that agreement, Russia took control of Lviv and western Ukraine. For the first time in 699 years, all of Ukraine was now under Russian rule. 2 years later, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Stalin had taken care to kill any general with the slightest competence lest they challenge his leadership, and of course Stalin was useless as a military strategist, so the Wehrmacht advanced eastward with lightning speed, reaching Kyiv in just 3 months. Many Ukrainians initially welcomed the Nazis, hoping Hitler would liberate them from Stalinist tyranny. Some Ukrainians enthusiastically bought into the anti-Semitic hatred so widespread at that time. And some Ukrainians unquestionably collaborated in the Jewish Holocaust. But the majority quickly realised that Hitler was just as bad, and throughout the war Ukrainian nationalists fought both the Nazis and the Reds. The strongest Ukrainian nationalist resistance was in the West which had been Polish territory until 1939. These people hadn’t lived through the Holodomor, and so were more fit to fight. In fact in western Ukraine, nationalist resistance against the Soviets continued into the 1960s.

In 1945 Stalin insisted that Poland permanently cede to the USSR the land that he had taken under the Nazi-Soviet pact. Poland would be compensated with land from Germany. And so, the nation of Poland was shifted sharply westward, and for the first time in 699 years, the whole of Ukraine was politically united with Russia, including Lviv and surroundings. Fortunately the extreme brutality of the Holodomor was not repeated. Although higher education was all in Russian, western Ukraine remained primarily Ukrainian-speaking. Kyiv was (and is) a bi-lingual city. But further east, many ethnic Ukrainians spoke no Ukrainian at all until recently. Since 1991, all school instruction has been in Ukrainian, but many adults from the east still struggle to speak it.

In 1954 (the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s initial absorption into the Russian Empire), Khrushchev transferred the Crimean Peninsula from Russia to Ukraine. Although adjacent to Ukraine, Crimea had never been part of Ukraine previously. Russia had annexed what was then the Crimean Khanate in 1783. In 1945 Stalin falsely accused the indigenous Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis, exiled most of them to deserts in Kazakhstan and murdered the rest. That left the peninsula largely unpopulated, and a mix of Soviet peoples (mostly Russians) filled the gap. Like the rest of eastern and southern Ukraine, Crimea remained primarily Russian speaking after 1954. By 2013 Crimea was roughly 65% ethnic Russian (concentrated in the city of Sevastopol, home of the Soviet and then the Russian Black Sea Fleet), 15% Ukrainian, and 12% Tatar (a very few who made it back from Kazakhstan alive) plus some Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Belarussians and others.

When the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, the impoverished and preoccupied Russian government made no provisions at all to help millions of Russians suddenly stranded in other former Soviet Republics. Whether trying to stay within these newly independent countries (many of which were hostile to them), or to find some way back to Mother Russia, these ethnic Russians in the “Near Abroad” were on their own. This was to become a problem in several places.

Crimea was a paramount Russian concern. Russia’s Black Sea fleet is based there, and Russians have a profound emotional attachment to it due to the enormous blood shed in conquering and then defending it, both in the Crimean War (against Britain, France and Turkey in the 1850s) and World War II. After independence, Ukraine immediately agreed to permanently lease the naval base to Russia. Under the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, Ukraine gave up all the nuclear weapons on its soil, in exchange for Russia explicitly recognising Ukraine’s current borders and the US pledging to guarantee Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Read that again.

Map#7 above: Ethnic Russians as a percentage of the population by region. (Do NOT confuse ethnic Russians with Russian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians!) The Donbas (Donetsk Basin, a heavily industrialised area rich in natural resources) has a higher ethnic Russian percentage than does the Donetsk region as a whole.

Ukraine had always been an ethnic and linguistic continuum, Ukrainian in the west and gradually getting more Russian with each mile east that you travel. Think of three distinct groups:

Ethnic Ukrainians who speak Ukrainian as their first language. Older people also speak Russian, though many don’t like to. Some younger ones raised after independence don’t speak Russian. They are concentrated in the west and centre of the country.

Ethnic Ukrainians who speak Russian as a first language, very common east of Kyiv. Many also speak Ukrainian, but some don’t. Many thousands of them fled west to the relative safety of Lviv and other cities, only to find hostility and distrust because they speak the language of the enemy. Although many still aren’t learning Ukrainian as fast as some people would like, they have proven their loyalty many times over. In film footage from the trenches, I am often struck by the Russian-Ukrainian pidgin dialect commonly spoken by Ukrainian troops so everyone can understand.

Ethnic Russians (mostly mono-lingual). Where they are a small minority, they are not a problem. But in the easternmost regions where they are heavily concentrated, thousands have proven themselves actively, violently opposed to Ukrainian independence. These heavily Russian areas are a cancer that will destroy Ukraine from within unless the cancer (which is basically the lands Putin took in 2014) is cut out.

Very quick summary of post-independence Ukrainian politics:

Politics have broadly followed the ethnic divide, with western Ukraine strongly in favour of joining the EU, and the East historically more aligned with Russia. Until 2014, a clear majority opposed joining NATO, preferring to be economically western, but politically a neutral “bridge” between East and West. Independent Ukraine’s first few leaders prioritised friendly relations with Russia, while also seeking to also build bridges to the West as a second priority. This was to change when Russia attacked Ukraine, as shown in the chart below:

In the 1990s, Ukraine was poor, corrupt and dissatisfied, but so was Russia. Then oil prices started jumping around 2000 due to booming Chinese demand, and Russia catapulted into high growth while Ukraine was left behind. With poverty and corruption rife, growing popular resentment led to the Orange Revolution in 2004, which elected avowedly pro-Western leaders for the first time. Putin and the majority of ethnic Russians were (and still are) convinced that this was all a Western plot to deny Russia its god-given imperial greatness. Putin set about undermining the new government by any means necessary, including poisoning the newly elected president Yushenko. He needn’t have bothered -- the pro-Western leaders proved their own worst enemies, unable to get control of corruption or to improve living standards. In 2009 the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovich won election, albeit in order to win he explicitly promised to put Ukraine on track for eventual EU membership, a promise which was then endorsed by a supermajority of the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament).

2011-12 was a pivotal moment in Russia, when Putin announced that he would amend the constitution to abolish term limits and become eligible to be president for life. Massive demonstrations put him on thin ice, but he was saved when he launched his anti-LGBTQ campaign with the fanatical support of the Russian Orthodox Church. This is when Russia really became a full-fledged dictatorship with avowedly imperial ambitions.

In 2013, under extreme pressure from Putin, Yanukovich reneged on his promise to lead Ukraine toward the EU, and said Ukraine would seek an economic union with Russia instead. Protests erupted, most famously at the Maidan square in Kyiv. When the protests wouldn’t stop, Yanukovich’s agents shot at the crowd repeatedly, killing over 100 people.

Maidan Nezalezhnosti (“Independence Square”) during the Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity in 2013-14 (photo by Sergei Chuzavkov, AP)

In the ensuing days of “Euromaidan” the demonstrators began firing back, assisted by sympathetic police and soldiers. In February 2014, just as Russia was hosting the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Yanukovich was forced to flee to Moscow. In a special election, billionaire Petro Poroshenko was elected president of Ukraine on a pro-Western platform. Putin promptly invaded Crimea and Ukraine’s easternmost provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk, on the pretence of protecting the large ethnically Russian populations there. Ethnic Russians formed militias that assisted the invasion, and the Ukrainian army proved completely incapable of responding, so Putin easily captured these lands. Eventually a static, low-grade war developed along a frontline that barely moved.

Evolution of Ukrainian attitudes to joining NATO — look how opinions changed in 2014 and 2022

With this development, a clear majority of Ukrainians began for the first time to favour joining NATO, and the majority in favour of EU membership increased. But with Ukraine now engaged in an active territorial dispute, it was ineligible to join either organisation. While the Ukrainians’ refusal to accept any loss of territory is understandable, it was a big mistake in my view. Had they accepted the losses of these lands with their disloyal Russian populations in 2014, and sought EU and NATO membership under their diminished de-facto borders in existence from 2014-22, they would have been eligible. And had they joined NATO, Putin would never have invaded again in 2022. I personally see no scenario where Ukraine ever gets back the lands they lost in 2014, nor should the want to. The violently disloyal Russians on those lands would destroy Ukraine from within.

Map #8 above: Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine’s most heavily Russified territories — Crimea, and the area around the Donetsk Basin (Donbas). Territory taken is in pink.

From 2014-19 Petro Poroshenko proved not just inept at reform, but staggeringly personally corrupt, and his popularity declined steadily. Meantime, an actor named Volodymr Zelensky was starring in a popular television show called “Servant of the People”, about an ordinary man who suddenly becomes president and starts building an honest government. Both Zelensky and the viewers started to take this idea seriously. As the 2019 elections approached, Zelensky declared his candidacy. Watching all this very closely, Putin judged (correctly) that Poroshenko would lose his 2019 re-election bid, and he expected that a newbie like Zelensky would be more malleable (Western observers also thought Zelensky would be more pro-Russian).

Zelensky did win, but proved as ardently pro-Western as any of his predecessors. Also in 2019, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church declared Autocephaly (independence) from the Russian Orthodox Church under which it had been subordinate for over 700 years. The global Orthodox leadership in Istanbul accepted this, but the Russian church leaders were enraged. And by this time the Russian church had become a critical ally and constituency for Putin, as already explained. With the Russian Church’s active support, Putin decided that if he couldn’t control Ukraine quietly from the sidelines, he would invade and subjugate it outright, eradicating any concept of Ukrainian nationality to permanently “fix the problem”. It played out as follows:

Map #9 above: Putin’s 2022 invasion of the Ukrainian heartland

A large army group struck from Belarus to Kyiv, but was repulsed after a month of bloody fighting and slaughter of civilians in Bucha and Irpin by Russian forces. Parts of Sumy Region were taken, but liberated within 45 days. Kharkiv (Ukraine’s 2nd-largest city) was initially half-surrounded, but Ukraine retook all land in blue in their counteroffensive in August-September 2022. In short, Putin’s attacks on the ethnic Ukrainian heartland were a complete failure.

Russia was more successful down South, where they took and held a wide band of land between Crimea and Donetsk. Mariupol and surroundings hiave a large ethnic Ukrainian majority. But with Russia already controlling the neighbouring land on three sides, and its location so far from Ukrainian supply lines, even the exceptional bravery and resilience of the Ukrainian defenders couldn’t get the job done. Mariupol is the place where hundreds of civilians were sheltering in the city’s main drama theatre with a huge tarpaulin on the roof saying “ДЕТИ” (“children”). Russia bombed it, killing dozens.

The front then stabilised. By the time of Ukraine’s 2023 counter-offensive, land mines and drones made significant progress impossible for either side.

For three years now the front line has hardly moved. In 2024 Russia sacrificed around 500,000 dead or maimed to take 0.6% of Ukraine’s territory

C. 20% of Ukraine (the red area) is now under occupation.

Many people have criticised Biden for failing to prepare Ukraine for war. I think Biden’s approach before the Russian invasion was near-flawless. No one thought the Ukrainian army could hold out in a conventional war, so Biden supplied Ukraine with large quantities of Javelin anti-tank missiles and other weapons and tactics that would be very useful in the guerilla war that most experts expected. And when Putin was gearing up to invade, Biden tried repeatedly to warn Zelensky, but the Ukrainian government insisted that no, Putin would never be so stupid as to invade the ethnic Ukrainian heartland. So prior to the invasion, Biden did all that anyone reasonably could. It’s what Biden did after the invasion that was inexcusable.

When Putin did invade, and Ukraine astonished the world by stopping the Russians just outside Kyiv and Kharkiv and then throwing them back, Biden’s administration adjusted well and began providing weapons appropriate to the conflict that emerged. Initially it was reasonable of Biden to supply limited weapons with restrictions on their use, to show Putin that the US did not want to escalate into World War III. But Intelligence quickly picked up that Putin’s boss Xi Xinping (ruler of China) had warned Putin not under any circumstances to use nukes. And anyway, Putin would never do anything that threatens his own personal survival. So Putin’s endless threats of nuclear war were and are empty. Especially when it became clear that Trump would probably win the US elections, Biden should have provided vastly more weaponry with no restrictions on its use. He refused. That was inexcusable.

So now the war is in deadlock. In short, Russia is spending money at an unsustainable rate, while Ukraine is losing soldiers at an unsustainable rate. The Western media speaks constantly of Ukrainian towns under threat, but if you follow the news over time you’ll see that it is the same towns described over and over for months on end as “under threat”, until finally Russia takes them one every 9 months or so, having sustained enormous losses. The front moves at much less than a snail’s pace — a snail departing from Donetsk in February 2022 and moving at a “snail’s pace” could have arrived in Vienna by now.. For a good assessment, see this analysis published by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in June 2025.

In all of 2024 Russia captured an additional 0.6% of Ukraine’s territory at a cost of around half a million dead or maimed. But while Russians hate conscription, they couldn’t care less about seeing their countrymen die as highly paid volunteers. Over 1,000 Russians die at the front every day, but Putin easily recruits replacements. The problem is war spending, which has pushed interest rates sky-high, with civilian industrial investment lmot completely crowded out. With Trump in office, Putin knows he can kill unlimited Ukrainian civilians without repercussions. So Putin has ramped up his war effort to even more unsustainable levels (much like Germany’s Final Offensive in the summer of 1918) to try to force a quick surrender. Will it work? Time will tell.

Ukraine, for its part, went through initial terror during the invasion, followed by euphoria when they successfully defended Kyiv and Sumy while recapturing significant lands near Kharkiv in their surprise offensive in August-September 2022. By year-end 2022, 73% polled favoured fighting to total victory.

2023 was then a bitter disappointment, as their long awaited offensive became a complete failure with high casuaties (by the time it finally started, Russia had built defences that were virtually impregnable in the absence of air support).

2024 was a year of grim resolve, as they inflicted over half a million casualties (dead or maimed) against Russia and destroyed massive amounts of heavy equipment, with relatively light casualties.

But the time from Trump’s victory until now has been deeply depressing, as their international coalition has weakened while Russians are developing at least minimal competence in fighting a war of this nature. Russia’s drone attacks on both the front and Ukraine’s cities have skyrocketed in both quantity and accuracy. And instead of sending large mechanised columns to be destroyed, Russia is using more effective tactics with small groups of infantry. In a recent poll 69% of Ukrainians now favour a negotiated settlement, but the vast majority reject that without multinational security guarantees including foreign troops (Europe’s vastly undermanned and underequipped infantries would be next to useless, but Europe’s air forces would be a complete game-changer).

Russian opinion polls also show a significant and growing majority who want a negotiated settlement. They are tired of endless flight delays and airport closures due to Ukrainian drone threats. They are worn down by Ukrain’s very successful attacks on oil refinieries, which have pushed retail gasoline prices in Russia up 50% in 2025 YTD to West European levels, in a country where the average wage is $100 per month. And that’s if you can get gasoline ta all — petrol queues now stretch for miles all over Russia.

Ukraine now has a manpower crisis. They have already reduced the minimum draft age from 27 to 25, and may have to reduce it further. Previously men over 18 were banned from leaving Ukraine. Ukraine has lifted that ban and also eliminated all penalties against young men who return home having broken that law earlier, hoping that on net this will bring more men into the army than it will lose. Ukraine may have to reduce the draft age even further. On the one hand, Ukrainian civilians whom I speak to are absolutely resolved never to surrender. But on the other, too few of them are willing to go to the front themselves. Extremely good news is that Ukraine’s newest drones are hammering Russia’s oil industry, which funds the war. It’s a question of which will run out first — Russian money, or Ukrainian troops? Only economic crisis will bring Putin to the negotiating table. This can be achieved either by cutting off Russia’s oil exports, or a global oil glut pushing the price of West Urals Crude substantially below $60 per barrel for a long period. Conversely, a major new war in the MIddle East would jack oil prices into the stratosphere and allow Putin to fund the war indefinitely.

It’s worth noting here the hypocrisy of Donald Trump cricitising India’s purchases of Russian oil. That is something Biden and NATO actually encouraged India to do. At the start of the war, they realised that if Russian oil exports were cut off, a global energy crisis would send oil prices skyrocketing — that would push the West into recession, and whatever oil Putin DID smuggle out would earn a huge profit. So they told India “fine, we welcome you buying crude oil from Russia, but only crude oil (nothing refined) and at a steep discount. Then India, you refine it all and sell it on the global market at the normal price. So India you earn a fortune, Russia gets bled, and the world economy doesn’t go into recession”. The Indians were understandably confused and annoyed when Trump started attacking them over this.

And at the same time, Putin is fighting a dirty war on other fronts – his efforts to hack western European computer, banking and defence systems and interfere in Western elections are well known. Putin is also trying to use Ukrainian refugees to turn European governments and people against Ukraine. Ukrainian refugees have already been arrested for attempting terrorist acts – they are either economically desperate and lured by high Russian payoffs, or Putin is threatening their relatives in occupied Ukraine if they don’t cooperate. And at the same time he’s using every propaganda tool available to him (including sympathetic networks like Fox News, sympathetic European political parties, and the Russian diaspora who are in many cases fanatically pro-Putin) to spread propaganda that all Ukrainians are nazis and terrorists.

For politicians like Orban of Hungary, Fico of Slovakia and Trump of the US, Putin is a compelling role model – democratically elected and re-elected initially, now president for life with all political opposition either dead or exiled. And all of these leaders find it convenient to disdain Ukraine’s desire for democracy and NATO membership. Poland is a rare exception where the main Trump-like populist political party is broadly pro-Ukrainian. I think the Poles’ exceptionally high empathy for Ukraine comes from their own experience. After Poland was re-established as an independent country in 1919, nationalists in both Germany and Russia saw its very existence as a national insult, and Stalin and Hitler took great delight in carving it back up in 1939. Now Putin sees Ukraine as both a personal and national insult whose entire national identify must be eradicated — Poles know what that feels like, and what it leads to. They also know that ife Putin wins in Ukraine, they are next. By contrast, the main who just barely lost Romania’s recent presidential election had stated that Ukraine is not a country and Putin should do whatever he likes with those people. That level of antipathy goes back to the 1800s, when Eastern Europe had a distinct ethnic pecking order in which the Austrians sat at the top and Ukrainians very much at the bottom.

Ukrainians fully understand that they are in a war of national survival. In 1922 Ukraine surrendered to Russian domination, and within 10 years, millions of them had been starved to death in the Holodomor. Much more recently, Russia has abducted over 20,000 Ukrainian children from captured territories, and is indoctrinating them in Russia to fight against their own families. A few children who could not be turned were released, but only after prolonged, severe torture. Anyone caught speaking Ukrainian in Russian-controlled territory disappears. And Russia slaughtered over 1,300 civilians in just four weeks of occupation of the Kyiv suburbs of Irpin and Bucha in the early days of the war. Ukrainians know that if they surrender this time, it will likely be at least another 100 years before they get another chance, and by then they may be wiped out as a people. Putin seeks not a genocide, but an ethnocide — the complete destruction of a national identity.

THE BEST DEAL THAT I THINK UKRAINE CAN GET UNLESS PUTIN DIES:

US guarantees are worthless, and NATO is too divided to matter, with Slovakia and Hungary vetoing any serious assistance to Ukraine. Ukraine and its allies need to accept that. Ad hoc Coalitions of the Willing are all that matter now. And don’t obsess about European ground troops — they are severely underequipped, undermanned, and in no way combat-ready, but Europe’s air forces could dominate the skies and neutralize the Russian war machine in a matter of days.

Putin demands the entirely of the 5 provinces that he has invaded, which would force Ukraine to abandone extensive fortifications and leave Putin with an open road to Kyiv. That is obviously out of the question.

Map #10 above: The current frontline

In the northeast and down south in the Crimea Peninsula, freezing the border at the current line of control is a good option. Ukraine should gladly give up Crimea, Luhansk, and most of Donetsk – all loaded with ethnic Russians who would destroy Ukraine from within. The cancer MUST be cut out. Ukraine has NO FUTURE with a violently rebellious ethnic Russian population still inside it. Forget about the Donbas’ national resources; Ukraine’s future is in high tech

In between those areas, freezing the border at the current line of control would be a bitter pill for Ukraine to swallow, losing substantial ethnic Ukrainian lands in Kherson and Zaporozhiya regions and requiring the mass resettlement of vast numbers of Ukrainians there. But this should be considered because it would leave Ukraine with heavily fortified, defensible borders, which in western Zaporozhiya and throughout Kherson would be along the massive, naturally protective Dnipro River. Under no circumstances should Ukraine offer this sacrifice up front, but it is a fallback position that needs to be in the potential mix. Resettlement would have to be funded by the EU and the UN High Commission on Refugees.

Regardless of where the new border will be, there must be a full accounting and return of abducted Ukrainian children, POWs and civlian detainees.

Russia will have its own big problems when the war ends, even if they win. Putin has used his oil money to create an army of several million men who earn very good money, some of them ex-convicts, many with no employable skills other than killing, who will eventually come home to an economy that will collapse when war spending stops, to find they have no job prospects and no one cares about them.

If you want to keep up on the news of the war, I highly recommend subscribing to the Kyiv Independent and The Moscow Times (now published from the Netherlands). The BBC and Al-Jazeera are also good.

Slava Ukraini!